In this final part of the series on the Hebrew calendar we will discuss Counting the Omer, which refers to the counting of days from the Feast of First Fruits to determine the date of the Feast of Weeks. If you’ve not yet read the previous articles in the series, you can find them here. Part 1 explained the importance of having a right understanding of God’s calendar and defined the terms evening and morning. Part 2 discussed the Biblical day and when it starts, part 3 focused on when a month begins and part 4 did the same for a year. Part 5 introduced the concept of an agricultural year and showed how it differs from a calendar year and how it is the year reckoning the Bible uses for the Sabbath and Jubilee year cycles and Daniel’s 70 weeks.

When it comes to Counting the Omer there are two main methods and several less popular ones. The two main ones are that of the Pharisees, who started the count from the day after the first day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread (that is, on the 16th day of the first month, which is the method in present day use), and that of the Sadducees, who started from the day after the first weekly Sabbath day during that feast. The differences come from different interpretations of the text in Leviticus:

Leviticus 23:15-16. ‘And you shall count for yourselves from the day after the Sabbath, from the day that you brought the sheaf of the wave offering: seven Sabbaths shall be completed. Count fifty days to the day after the seventh Sabbath; then you shall offer a new grain offering to YHWH.’

The Pharisees considered the first “Sabbath” to be the High Sabbath at the beginning of the Feast of Unleavened Bread, whereas the Sadducees considered it to be the weekly Sabbath. Having looked at both sides of the argument it appears the text could legitimately be referring to either, so approaching the question from that angle is inconclusive. It is, in fact, because the text is inconclusive that there are different views on the topic.

One problem with using the weekly Sabbath is that it was never given for the purpose of calculating the feast days; yet in Genesis 1:14 the sun and moon specifically were. A related problem is that it’s a relative measurement. The Bible says, concerning the Sabbath, that it should be a day of rest every seventh day, but it doesn’t state when the first Sabbath should be. If we were to use a different day for our seventh day (there is no stipulation that it should coincide with the seventh day of the Roman week, and originally it might not have) the dates of First Fruits and the Feast of Weeks would be different. Such a possibility doesn’t appear tenable given the Biblical principal of using the sun and the moon for reckoning feast dates. For the remainder of this article we’ll focus on the other method that considers the first day of Unleavened Bread to be the Sabbath referred to in Leviticus 23:15.

The following passage from Joshua is instructive as it documents the very first time this feast was observed:

Joshua 5:10–11. Now the children of Israel camped in Gilgal, and kept the Passover on the fourteenth day of the month at twilight on the plains of Jericho. And they ate of the produce of the land on the day after the Passover, unleavened bread and parched grain, on the very same day.

Note that eating the produce of the land was prohibited until after the first fruits offering:

Leviticus 23:14. You shall eat neither bread nor parched grain nor fresh grain until the same day that you have brought an offering to your God […]

The passage in Joshua is clearly a reference to this requirement of the law having been met, and therefore the offering must have been made on that day. As Joshua says this was the day after the Passover, and Leviticus says it should be the day after the Sabbath, those who follow the weekly Sabbath method claim that the Passover in Joshua 5:10 must have fallen on the weekly Sabbath, and therefore the day after the Passover was also the day after the Sabbath, despite that not being stated. It’s possible, but it’s a weak argument and begs the question as to why Joshua mentioned that it was the day after the Passover if that was inconsequential.

For the alternate view that the Sabbath is the High Sabbath on the first day of Unleavened Bread, there is some evidence that this could be correct. The first day of Unleavened Bread is described as a “holy convocation; you shall do no customary work on it” (Leviticus 23:7). The descriptions of both the Day of Atonement and the Feast of Tabernacles refer to similar holy convocations as sabbaths:

Leviticus 23:27-28,32. “Also the tenth day of this seventh month shall be the Day of Atonement. It shall be a holy convocation for you; […]. And you shall do no work on that same day, […] It shall be to you a sabbath of solemn rest, […]

Leviticus 23:34-35,39. ‘The fifteenth day of this seventh month shall be the Feast of Tabernacles for seven days to YHWH. On the first day there shall be a holy convocation. You shall do no customary work on it. […] ‘Also on the fifteenth day of the seventh month, […] there shall be a sabbath-rest, […]

Both these special feast days are described in the same terms as the first day of Unleavened Bread, both are called sabbaths, and they are clearly not referring to the weekly Sabbath because they are on the tenth and the fifteenth days of the month—five days apart, not seven. Thus, there is a precedent from these feasts for holy convocation days to be called sabbaths.

Joshua later says that the offering was made the day after the Passover, which would mean that Passover must have coincided with the first day of Unleavened Bread. That this is so can be confirmed from Exodus:

Exodus 12:18. In the first month, on the fourteenth day of the month at evening, you shall eat unleavened bread, until the twenty-first day of the month at evening.

There is a seeming discrepancy here with the description of the Feast of Unleavened Bread in Leviticus:

Leviticus 23:5–6. On the fourteenth day of the first month at twilight is YHWH’s Passover. And on the fifteenth day of the same month is the Feast of Unleavened Bread to YHWH; seven days you must eat unleavened bread.

Using an evening-to-evening reckoning of a day there is no way to resolve this dilemma. However, as we’ve already shown that a day is from morning-to-morning it is quite understandable. The first day of Unleavened Bread spans two calendar days—the last half of the 14th and the first half of the 15th. This is yet more evidence that our earlier reckoning of the day is correct.

Joshua offered the first fruits offering on the day after Passover, which the book of Numbers confirms is the 15th day of the month:

Numbers 33:3. They departed from Rameses in the first month, on the fifteenth day of the first month; on the day after the Passover the children of Israel went out with boldness in the sight of all the Egyptians.

However, as the Passover was from the evening of the 14th until the evening of the 15th, it must have been in the evening of that next day that the first fruits offering was made and when they ate the fruit of the land for the first time. As Joshua 5:12 states that the manna ceased on the following day (the 16th) they would have had manna on the morning of the 15th, prepared the first fruit offering and meal during the day, then made the offering and eaten the fruit of the land in the evening once the Sabbath on the first day of Unleavened Bread had passed.

This means that, using this method, the 50-day count should begin on the 15th, not the 16th, as the Pharisees did and the Jews currently do. The evidence from Joshua 5 puts this beyond doubt for Joshua unquestionably presented the first fruits offering on the 15th of the month.

We earlier expressed doubts about using the weekly Sabbath to begin the count, and we’ve now shown that it’s quite plausible that the sabbath at the start of Unleavened Bread is the sabbath being referred to.

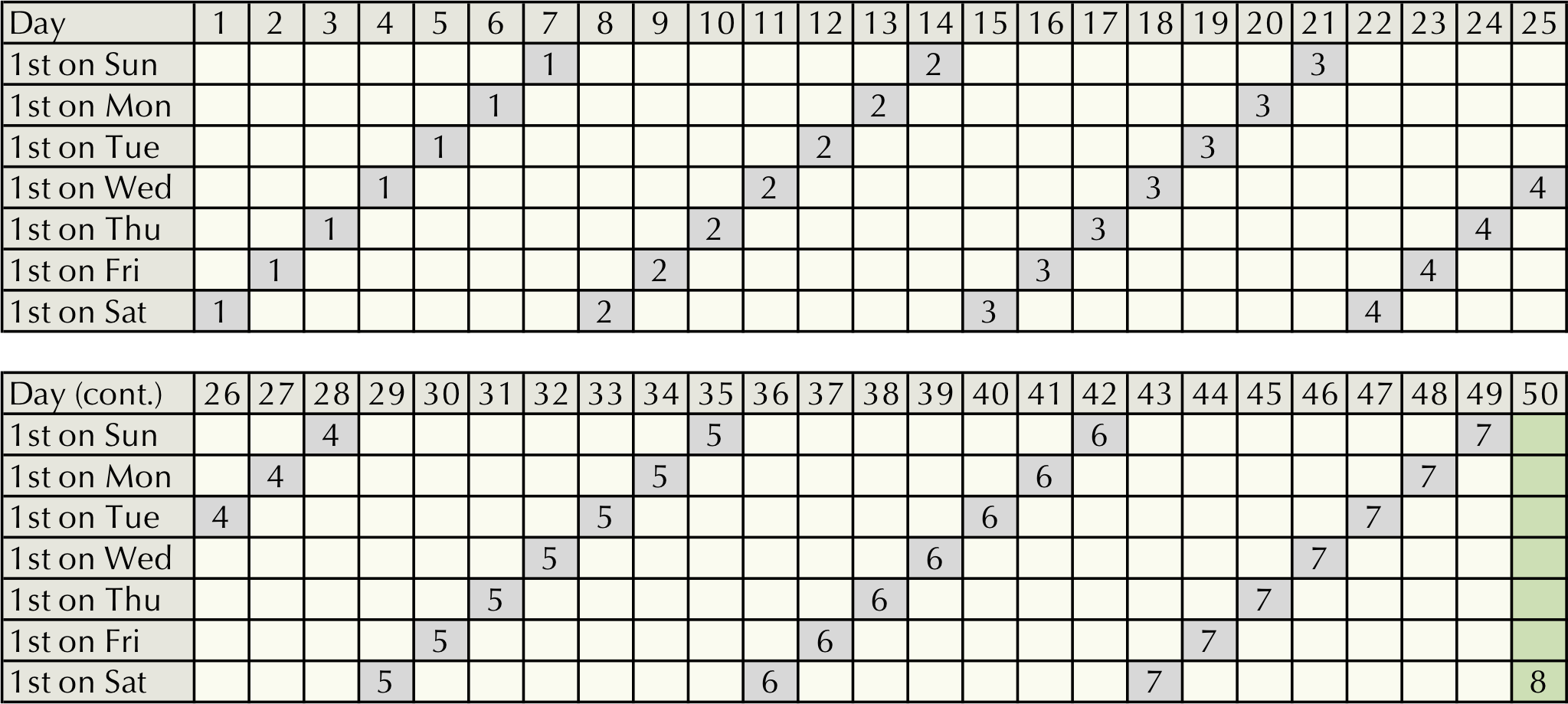

Further evidence in favour of the latter view is in the requirement to count 50 days. Leviticus 23:15 tells us that from the first day, seven weekly Sabbaths must be completed and verse 16 confirms that the offering of the Feast of Weeks must be after the seventh weekly Sabbath. The only number of days that one can count that will always fulfil that requirement, regardless of which day of the week the count starts on, is 50 days. That this is so is illustrated in the following chart.

In the above chart the number of completed Sabbaths are in grey, and the completion of the 50 day count is in green. Note that if only 49 days were counted, on occasions when the count began on the day following the Sabbath (on a Sunday) it would finish on the day of the seventh Sabbath and so seven full Sabbaths would not have been completed. And if 51 days were counted, on occasions when the count began on the Sabbath day (Saturday) it would finish on the day after the eighth Sabbath, and so eight, not seven full Sabbaths would have been completed. But counting 50 days always results in exactly seven full Sabbath days having been completed, regardless of where in the weekly Sabbath cycle the count begins. Although Leviticus 23:16 says to “count fifty days to the day after the seventh Sabbath” the definite article we’ve highlighted doesn’t appear in the text so it could read “count fifty days to a day after the seventh Sabbath”—both the literal text and the context suggesting the important element is that seven full Sabbaths have been completed.

Another important point is that Deuteronomy 16:9 says “begin to count the seven weeks from the time you begin to put the sickle to the grain” which is at the Feast of First Fruits. Therefore, as day one is the Feast of First Fruits, day 50 is actually 49 days later, and will fall on the same day of the week. If First Fruits happens to fall on a weekly Sabbath day then the Feast of Weeks will fall on a weekly Sabbath day too. That would be the eighth Sabbath but it is not counted among the seven for it would not be complete until after the Feast of Weeks was over anyway. There is no directive that this should not be for it is only customary work (that is, work related to your regular occupation, as per Leviticus 23:7) that is forbidden on Sabbath days. The practice of delaying feast days that fall on weekly Sabbath days is another Jewish tradition that is not scriptural.

In the current Jewish calendar the Feast of Weeks has a fixed date, which is the 6th day of the 3rd month. Using the actual solar/lunar calendar rather than a mathematical approximation, and basing our calculations on the aforementioned method, the Feast of Weeks can fall on either the 4th, 5th or 6th day of the 3rd month. As this date isn’t fixed, even though the start date is, this eliminates one of the criticisms against using this method—the criticism being that if the date is fixed, why wasn’t the date stated in the Bible as it is for all the other feasts? As the date is not fixed when using the correct calendar, this criticism doesn’t apply.

What is most peculiar about this method is that in 70% of years the number of days from the Feast of Weeks to the Feast of Trumpets in the seventh year is precisely 2,300 days. Any student of Biblical prophecy should recognise that number as pertaining to the antichrist (from Daniel 8:14) and it’s one of the ways we can confirm these dating methods are correct. In Delivered From Delusion we do further calculations based on the feast dates, the Jubilee years and the time periods given in scripture—1,260 days, 1,290 days, 2,300 days and 2,520 days—and using the correct Hebrew calendar we’ve been able shortlist four years in the next decade on which the 70th week can begin. That’s not to say those calculations confirm it will begin in the next decade, but we’ve also given other very compelling evidence to suggest it probably will.

If this is correct there is not very much time left at all. While we always need to be living our lives as if the end could be at any time there is no harm done if we are wrong. But if we are right the end really could be very soon and there is literally not a moment to lose. Get Delivered From Delusion now to see which dates the calculations mentioned above predicted and much, much more.

Back To: The Agricultural Year

You might also be interested in these series: